By Maxim Lott

FoxNews.com

Think mind reading is science fiction?

Think again.

Scientists have used brain scanners to detect and reconstruct the faces that people are thinking of, according to a a study accepted for publication this month in the journal NeuroImage.

this month in the journal NeuroImage.

this month in the journal NeuroImage.

this month in the journal NeuroImage.

In the study, scientists hooked participants up to an fMRI brain scanner – which determines activity in different parts of the brain by measuring blood flow – and showed them images of faces. Then, using only the brain scans, the scientists were able to create images of the faces the people were looking at.

“It is mind reading,” said Alan S. Cowen, a graduate student at the University of California Berkeley who co-authored the study with professor Marvin M. Chun from Yale and Brice A. Kuhl from New York University.

'You can even imagine, way down the road, a witness to a crime might want to come in and reconstruct a suspect’s face.'

- Alan S. Cowen, a graduate student at the University of California Berkeley

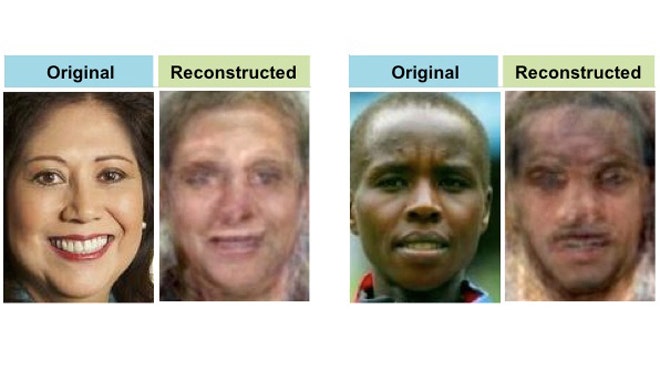

The study says it is the first to try to reconstruct faces from thoughts. The photos above are the actual photos and reconstructions done in the lab.

While the reconstructions based on 30 brain readings are blurry, they approximate the true images. They got the skin color right in all of them, and 24 out of 30 reconstructions correctly detected the presence or absence of a smile.

The brain readings were worse at determining gender and hair color: About two-thirds of the reconstructions clearly detected the gender, and only half got hair color correct.

“There’s definitely room for improvement,” Cowen said, adding that these experiments were conducted two years ago, though they only recently were accepted for publication. He said he and others have been working on improving the process in the interim.

“I’m applying more sophisticated mathematical models [to the brain scan results], so the results should get better,” he said.

To tease out faces based on brain activity, the scientists showed participants in the study 300 faces while recording their brain activity. Then they showed the participants 30 new faces and used their previously recorded patterns to create 30 images based only on their brain scans.

Once the technology improves, Cowen said, applications could range from better understanding mental disorders, to recording dreams, to solving crimes.

“You can see how people perceive faces depending on different disorders, like autism – and use that to help diagnose therapies,” he said.

That’s because the reconstructions are based not on the actual image, but on how the image is perceived by a subject’s brain. If an autistic person sees a face differently, the difference will show up in the brain scan reconstruction.

Images from dreams are also detectable.

“And you can even imagine,” Cowen said, “way down the road, a witness to a crime might want to come in and reconstruct a suspect’s face.”

How soon could that happen?

“It really depends on advances in brain imaging technology, more so than the mathematical analysis. It could be 10, 20 years away.”

One challenge is that different brains show different activity for the same image. The blurry images pictured here are actually averages of the thoughts of six lab volunteers. If one were to look at any individual’s reading, the image would be less consistent.

“There’s a wide variation in how people’s brains work under a scanner – some people have better brains for fMRI – and so if you were to pick a participant at random it might be that their reconstructions are really good, or it might be that their reconstructions are really poor, which is why we averaged across all the participants,” Cowen said.

For now, he added, you shouldn’t worry about others snooping on your memories or forcibly extracting information.

“This sort of technology can only read active parts of the brain. So you couldn’t read passive memories – you would have to get the person to imagine the memory to read it,” Cowen said.

“It’s a matter of time, and eventually – maybe 200 years from now – we’ll have some way of reading inactive parts of the brain. But that’s a much harder problem, as it involves measuring very fine details of brain structure that we don’t even really understand.”

The author of this piece, Maxim Lott, can be reached on twitter at @maximlott or at maxim.lott@foxnews.com

No comments:

Post a Comment